What does it look like to teach content-area skills in a math, science, or social studies classroom while also emphasizing social and emotional skills? How can those academic, social, and emotional competencies reinforce each other and strengthen learning? Experienced educators describe how they have built successful classrooms that demonstrate how teaching social and emotional skills is as important as teaching academic content.

A+SEL in Middle School Math

By Lisa Sassaman

Middle school math—it’s a topic that strikes fear into the hearts of both students and adults. As a Responsive Classroom practitioner for 18 years and a middle school math teacher for 14 of those years, I know that it does not have to be that way. By the time students get to middle school, many have negative feelings about math (and math teachers). While those feelings are real and should not be discounted, they can be changed. Intentionally embedding social-emotional learning into math content is not only possible but can be the key to changing those feelings.

Students who dislike math often perceive it as being filled with embarrassing errors. The use of anchor charts to remind students of the procedures to complete mathematical routines is one approach to help change that perception. Start by displaying the charts in a prominent spot in the classroom as the content is taught and practiced, and then move them to a reference location. Don’t cover them up. Refer to them often and model for students how to use the charts to guide their learning. As students use these anchor charts, not only do they learn the content correctly, but they also take responsibility for their learning while developing self-control and perseverance.

One of the most discouraging phrases a math teacher can hear is “I don’t get it.” Students often don’t have the words to express their frustration or confusion, but learning the skill of self-advocacy can help develop this aspect of assertiveness. Start by displaying sentence starters in the classroom for students to use when asking questions and working collaboratively. Model how to use those sentence starters so students hear them in action. I will never forget the first time one of my students said (while repeatedly glancing at the sentence starter out of the corner of her eye), “I don’t understand what you said. Could you say that in a different way?” We both stood a little taller at that moment.

When working in cooperative groups, provide sentence frames for disagreeing (“I understand what you are saying, but I disagree that ______ because _______ .”) and for keeping someone on task (“That’s interesting, but right now we should be talking about _______________________________.”). Model how to use and respond to these sentence starters when giving directions for the assignment. While monitoring cooperative work, providing students with feedback both on content and on their use of these sentence starters will keep the work moving forward and foster cooperation.

A+ SEL in Elementary Science

By Tally Lent

Over my 25 years of teaching elementary science classes, I have always found students to be natural scientists. Curiosity, observation skills, and motivation make each child an extraordinary learner, and a positive environment and developmentally responsive teacher plan will bring these three attributes to the forefront.

After I was trained in the Responsive Classroom approach 20 years ago, my success and enjoyment as a science teacher grew. I established ways of being and basic rules for my science classroom that my students would understand, whether they were five years old or 11 years old.

I begin each class with a brief meeting in which I go over the agenda and what I hope to accomplish in our 40 minutes together. One of my classroom rules is that students have to ask questions every day. With this in mind, some of the agenda items are purposefully open-ended to elicit questions and interest. It could be a big question that we might not know the answer to

or a small question that we could explore and discover the answer to together. Like scientists, it is through question asking and trial and error that students will make discoveries.

To feel safe and comfortable enough to ask questions, a student must be involved in the class and feel trust in peers and teachers. My science classroom is designed to foster that involvement through hands-on learning, daily science sharing from students, and journaling to record observations and reflections. Trust is built carefully and deliberately.

Students enjoy bringing in small natural or scientific artifacts or discoveries to share during our meetings. To prepare the class for sharing, I modeled and we practiced how to share and to give just enough information without going on too long. We had to practice empathy for our listeners to keep the sharing focused and engaging for listeners, and we learned to read their faces to make sure we were keeping their interest. The audience members also had responsibilities. I modeled and we practiced how to listen to the sharings and show that we were listening by keeping our eyes on the speaker and our attention quietly focused. Audience members had to actively listen so that questions or comments could be asked of the sharing student that added to our collective knowledge. Questions or comments were expected after each sharing, and the sharing student would call on peers and respond to them.

Sharing discoveries is a valued element of each class, and it develops our group dynamic and trust for each other. It takes just a few minutes of each class, but in those short moments, listeners effectively develop cooperation and self-control skills while the sharing student develops their assertiveness and voice.

After the science sharing portion of our class meeting, we move on to working in cooperative groups to explore concepts and skills with hands-on materials and experiments. These explorations don’t always work out as planned, and when they don’t, we reflect on what went awry and what we could have done differently. It may have been due to behavior within the small group, that the materials were difficult to work with, or it was a concept that was still in process and therefore our understanding was limited. Science class is a perfect place to reflect, revise, and try again: metacognition in action!

Active learning, immersed involvement in class, and exercising responsibility as a learner make science class lively and fascinating. Building social and emotional skills along with academic competencies allows for exciting learning opportunities to blossom. One example of this was the culminating exercise for a second grade class after its study of balance and motion. Using pipe insulating tubes, masking tape, and other found items, students were given the challenge of creating a room-size marble run. The marble had to be propelled by gravity alone and teams of students were in charge of different sections of the run. The science skills and the SEL skills that were essential to the successful completion of this challenge had to be developed and worked on over time, and second graders were ready for this task by late winter. My role was only to facilitate patiently. Students completed this challenge as a whole class, working together and listening and talking to each other with care. When that marble ran the course successfully, those students cheered as though they had won the Olympics!

Incorporating A+SEL in Social Studies

By Heather Young

Middle school social studies covers several disciplines: history, citizenship and government, geography, and economics. As a Responsive Classroom practitioner and passionate believer in the whole-child approach to education, I felt overwhelmed when thinking about how I could possibly cover all the standards and still have time to include social and emotional learning skills. I came to realize, though, that the content of our social studies curriculum offers many natural opportunities to embed the instruction and practice of social and emotional skills.

Addressing empathy is one way social studies educators can incorporate SEL skills during social study units. Present multiple perspectives of an event instead of just one side’s viewpoint. For example, while discussing the Boston Massacre of 1770, one might share with students that the same event was also known as “The Incident on King Street.” The class could analyze and compare the perspectives of American patriots and British loyalists in an attempt to find commonalities in descriptions of the event.

Active learning, immersed involvement in class, and exercising responsibility as a learner make science class lively and fascinating. Building social and emotional skills along with academic competencies allows for exciting learning opportunities to blossom.

We can also encourage students to practice a variety of cooperation and empathy skills by thinking about decisions people have made. Through activities that incorporate questioning, students can become more aware of the impact people’s actions can have on others, and how culture can impact attitudes and behaviors. This awareness allows them to practice empathy for people throughout history and around the world today. Students should consider questions such as these:

- What influenced this person in history to make a particular decision?

- How did that decision impact those around them?

- Viewing through our modern lens, how would we choose differently?

Another way educators can integrate SEL skills is through simulations. One example of a larger- scale simulation would have students play the role of U.S. senators and write bills about topics they are interested in. Bills should be on a national scale, which will encourage students to think beyond themselves and what changes they would like to see in the world. In this activity, students gather evidence to support their bill and then defend it to a Senate committee. Prompt students with questions such as these:

- How and where do you find evidence to support your ideas?

- How do we think about what someone against this bill might say, and how do we counter their argument?

This simulation not only provides students with a chance to practice finding evidence, an essential historical thinking skill, but also with a chance to practice a variety of assertiveness skills.

Committees of students debate the bills and decide whether or not that bill should make it to the “Senate floor.” This provides students with a forum to practice listening to opinions that are different from their own and working with others to come to a consensus.

The easy and successful way to incorporate SEL practice in your classroom is by allowing students to interact with each other in structured and collaborative ways. Whether it is through quick- partner or table chats during a geography lesson, a government simulation, or a group analysis of a historical event and its varying perspectives, students will benefit from these and other opportunities to engage with differing opinions. Utilizing the content of our social studies courses, educators can model, scaffold, and offer feedback on academic as well as social and emotional learning skills in the classroom.

Lisa Sassaman

Lisa Sassaman is a seventh and eighth grade math teacher at Lawrence Middle School in Lawrenceville, New Jersey, and has worked in education since 2002. Prior to teaching, Lisa worked as an environmental consultant. She was first introduced to Responsive Classroom practices after attending a workshop in 2003 and has carried those practices with her throughout her career as an elementary and secondary school teacher.

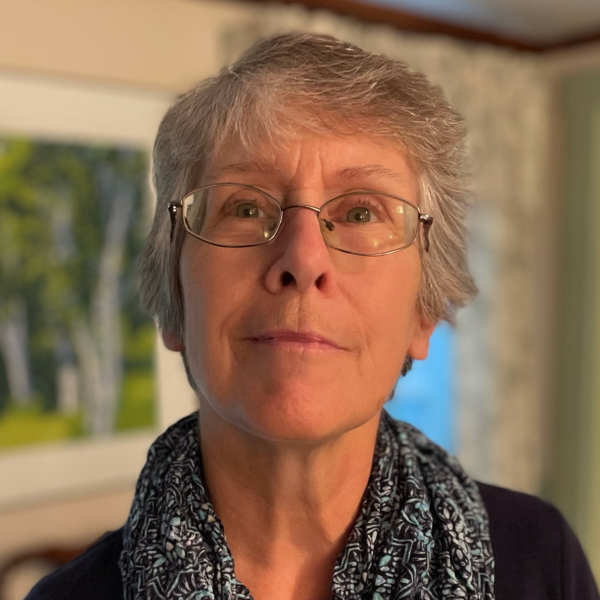

Tally Lent

Tally Lent has been an educator for 44 years, teaching everything from preschool to middle school science. She holds an MEd in curriculum and instruction from Lesley University.

For 26 years Tally served as lower school head and elementary science teacher at an independent school in central Massachusetts.

Heather Young

Heather Young began teaching in 2011 and is currently a middle school social studies teacher in the Minneapolis metro area. Before assuming her current role, she taught sixth grade reading and reading intervention for six years. Heather wrote the sixth grade sections of Empowering Educators: A Comprehensive Guide to Teaching Grades 6, 7, 8 (Center for Responsive Schools, 2021).