Need for School-Family Partnerships

As educators and parents, we must identify the current social-emotional state of our children and understand the critical role we both play in helping children build strong social-emotional skills such as learning to recognize and manage emotions, caring about others, making good decisions, and behaving ethically and responsibility while developing positive relationships and avoiding negative behaviors (Elias et al., 1997). Preparing today’s youth to handle life’s challenges is not a simple task. It requires a joint effort of the school and family following research-based strategies that support long-term social-emotional stability.

The current generation of students is not reporting positive social-emotional stability but rather is showing a high level of instability. The National Center for Education Statistics (2022) found that 87 percent of public schools reported negative impacts on students’ social-emotional development during the 2021–2022 COVID-19 pandemic. Schools in the United States have experienced an increasingly high rate of school violence, bullying, shootings, and youth suicide, and students have shown increased rates of depression, anxiety, stress, and feelings of fear, loneliness, and hopelessness (Zins et al., 2004). Students are under increased pressure to achieve in school, to help support the family with childcare and paying bills, to select a career before reaching high school, to perform well on the athletic field, and the list goes on. These pressures are drastically eroding the social and emotional state of students, impacting them both in school and post-school and leaving parents extremely concerned about their children’s mental health (Dorn et al., 2021). The rapid decline in the social and emotional state of youth combined with the high levels of anxiety and stress are having negative effects on student social-emotional development (McCarthy, 2019) and consequently having a toll on our nation.

Research Connection

For her book Thrivers: The Surprising Reasons Why Some Kids Struggle and Others Shine (2021), Michele Borba interviewed teenagers around the country through focus group discussions about why the current generation of students strives but fails to thrive. What she discovered is that this current generation of children is being raised to be strivers, pushed to pass tests, achieve goals, and study and work hard as they strive to reach the brass ring. Yet at the same time, Borba learned that these children are lonely and depressed; they are dealing with an abundance of anxiety.

The focus for success on this generation of students is on their cognitive abilities rather than on developing the “whole child” who can thrive. Borba (2021) identifies seven traits that characterize a thriving student: self-confidence, empathy, self-control, integrity, curiosity, perseverance, and optimism: This set of traits produces “mental toughness, social competence, self-awareness, moral strength, and emotional agility and reduces anxiety and increases resilience, so kids can cope with adversity, solve problems, bounce back, develop healthy relationships, and boost confidence” (p. 15).

Several research studies reinforce Borba’s conclusion that students will benefit from social-emotional teachings. The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL, 2008) published a meta-analysis research study that examined SEL-implemented school programs influencing 288,000 students. The study found positive results associated with these programs, with an 11 percent increase in achievement scores, higher academic student grades, and an increase in positive student behaviors and sense of well-being. The results of SEL teaching and implementation are only growing.

School-Family Partnerships

There is a plethora of research on the need for families and schools to partner to benefit children. Much of that research has found that positive social and emotional learning (and student achievement) strategies are more successfully implemented in a nurturing and supportive environment at school and at home (Zins et al., 2004). It is not enough for students’ social-emotional needs to be addressed only at school or at home, but a school-family partnership will have the most effective impact. However, some research reports that some parents feel threatened by the push for social-emotional learning at school, fearing that the school is interfering with the parent’s role of teaching morals and values (Zins et al., 2004). This is due in part to the purpose and push of the SEL programming in schools being misunderstood and not communicated clearly with parents as a home-school partnership whose goal is to increase dramatically the positive social-emotional effects on students. Rather than assign the task of teaching social-emotional skills to just one setting, the home or school, taking steps to cooperatively develop SEL skills in both environments will maximize the efforts. Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory and Epstein’s theory of overlapping spheres of influence support family-school partnerships and their ties to increased student achievement (Galindo & Sheldon, 2012).

Miller (2022) explored “how schools communicate and engage with families in online/blended learning environments to support students’ social-emotional well-being” (p. 37). This study found that while educators had great intentions and believed in the importance of family-school partnerships, the stress of time and multiple learning contexts negatively influenced their efforts spent in establishing and growing family-school partnerships. Hence, although the school-family partnership and family engagement with schools are important, the task of establishing this partnership needs to have simple, doable strategies for implementation.

Strategies for Strengthening Social-Emotional Learning

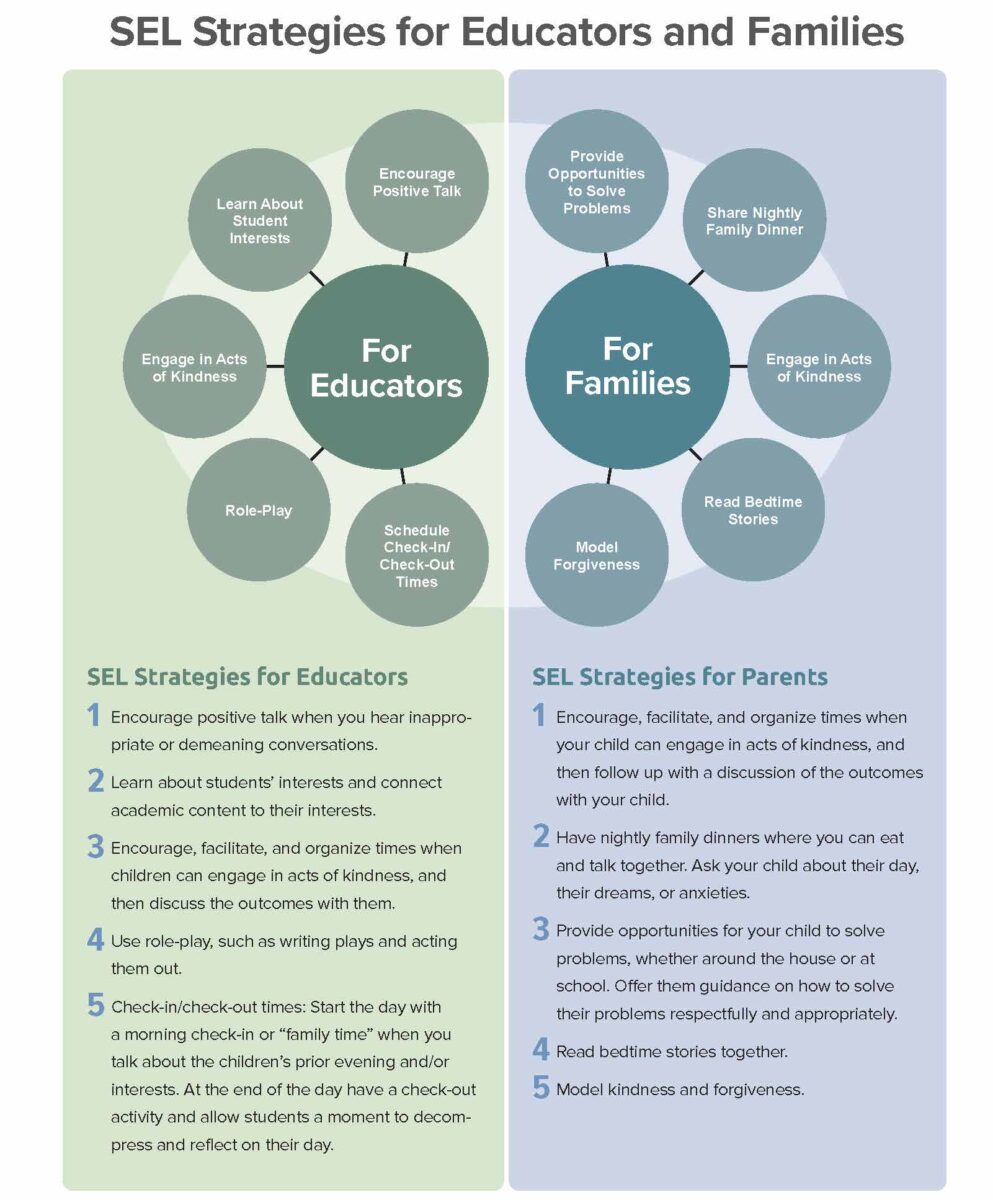

Learning to address the social-emotional needs of students is not an easy task for parents or educators. Sometimes even just identifying what these needs are can be daunting. In fact, educators and families are often so overwhelmed with knowing how to support a child’s social-emotional needs that they find themselves paralyzed and unable to begin. Parents and educators may blame each other, or ignore or fight with one another out of frustration with their inability to move into action to help the students. While this is all too common, it is of course not healthy for school-family partnerships and certainly not for children who desperately need guidance with social-emotional skill development.

Research has proven that when parents and family members understand SEL skill development they are more willing to partner with schools in teaching SEL skills at home, forming a parallel partnership that will produce lasting successful outcomes (CASEL, n.d.-b). The extension of social-emotional skill development at home gives students real-life application practice along with more significance and meaning behind the SEL skills (Cultures of Dignity, 2022). Simple tasks such as families having conversations at the dinner table, running errands and doing chores together, and talking to different people in the community are all ways that families can teach SEL skills through everyday experiences. Incorporating SEL skills into everyday experiences creates depth and meaning behind student application (Thorson, 2018).

Many researchers recognize that a strong bond between home and school positively influences a child’s growth and development (Edwards & Alldred, 2000; Epstein et al., 2009; Henderson & Berla, 1994; Richardson, 2009; Sanders & Sheldon, 2009). This family-school bond or partnership can positively impact and influence a child’s social-emotional needs and skill development. Families know their children better than anyone and have firsthand knowledge of their child’s needs. Educators are experienced and trained in providing social-emotional strategies that are necessary to meet a child’s social-emotional needs. A partnership between families and educators provides a strong foundation for students to achieve their maximum potential in academics and social-emotional skill development and application (National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments, 2022).

Many strategies are available for SEL development, but there are three strategies in particular that produce positive results when implemented in a family-school partnership:

- Using teachable moments

- Actively engaging in role modeling

- Accessing support services

Teachable Moments

Teachable moments can be used to teach and reinforce the rewiring of brain responses. Scientists have found that the human brain changes throughout one’s life and is moldable (similar to plastic) (Voss et al., 2017). When a new brain pathway is reinforced over and over, the new way of thinking becomes second nature. This process, called neuroplasticity, is the means by which the brain is rewired by forming new connections and weakening the old ones (Voss et al., 2017). Parents and educators can use those moments when students are not making good choices and teach them—at that moment—what is right from wrong, or positive versus negative.

Any argument or misbehavior can be a teachable moment if the guardian or teacher uses that moment wisely. When we think of teachable moments, we may believe that only coaches are known for them, especially in sports movies. However, coaches should not be the only ones known for teachable moments. Educators may find these moments when an opportunity presents itself for the teacher to deviate from the lesson plan for a moment in order to take advantage of something that activates a student’s interest. Making a detour from the lesson plan should be considered if there is a social-emotional need and the time is used wisely to provide this support.

Parents and educators must look for those teachable moments and reinforce positive decision-making while at the same time protecting the child’s emotional safety. Children will make wrong decisions, but it is the role of parents and educators to hold them accountable for their actions by teaching them the appropriate response. For example, if a child draws on the wall, instead of responding by yelling and screaming (which puts a child’s emotional state at risk), take that moment to teach about vandalism and the child’s responsibility in taking care of their environment. Can there be a punishment? Absolutely! As Cline and Fay (2020) have suggested, consequences will more often teach a child a lesson much better than aggressive words, undermining threats, or physical abuse (p. 37). The difference is that we still care about the child’s emotional well-being and stability. Empathy should be shown while providing the punishment (Cline & Fay, 2020), and when this is done, the child is able to learn, grow, and sustain future challenges.

Role Modeling

Borba (2021) states, “Kids who remain upbeat about life despite uncertain times have parents who model optimism, so be the model you want your kids to copy” (p. 255). As adults, we quickly forget that children are watching us and our reactions to life’s situations. Children tend to learn through role modeling whether we realize they are or not, and it can be an effective strategy for teaching social-emotional skills to children at school or in the family environment. This modeling will be most effective, however, if it is happening in both environments simultaneously.

Morgenroth et al. (2015) reviewed the theoretical framework behind the motivational theory of role modeling, examining the how and when behind role modeling, and found that role modeling was shown to have a direct positive influence on one’s goals and motivation. Research by Kearney and Levine (2020) found that there are positive influences on students’ educational performance and career decisions when students view their teachers as role models, especially in terms of teacher gender and race. The power of role modeling can be used to motivate, reinforce goals, and facilitate the adoption of new goals (Morgenroth et al., 2015), even when demonstrating and reinforcing SEL implementation.

Part of a child’s brain development stems from their interactions with the world around them as well as their social interactions with others. These social interactions suffer when bonds with others are threatened or broken, as the well-being of a child is highly influenced by their connections with others (Head Heart + Brain, n.d.). Building upon these connections with others to teach strong SEL skills is a strategy with positive results and benefits. In an interview with Scientific American, neuroscientist Matt Lieberman notes that “rather than being a hermetically sealed vault that separates us from others, our research suggests that the self is more of a Trojan horse, letting in the beliefs of others, under the cover of darkness and without us realizing it” (Cook, 2013).

Support Services

It is not uncommon for educators and families alike to work diligently and relentlessly to meet the various needs of their children, including social-emotional ones. However, both have expressed the concern that they are at a loss most of the time when it comes to providing SEL support (Sawchuk, 2021). Based on our past experience as administrators and from personal experience, we believe that this can often be attributed to the lack of knowledge about SEL support available for classroom teachers and families. For students and families to be successful at meeting the needs of children, wraparound services must be available and accessed by both educators and families. Many SEL support services exist for educators and families.

SEL Curriculum

According to the Collaborative for Social, Academic, and Emotional Learning’s framework, “SEL is the process through which all young people and adults acquire and apply the knowledge, skills, and attitudes to develop healthy identities, manage emotions and achieve personal and collective goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain supportive relationships, and make responsible and caring decisions’’ (CASEL, n.d.-a, para. 2). Schools are adopting social-emotional curricula to supplement the Common Core standards. Educators are well aware of Maslow’s developmental stages and understand the importance of meeting a child’s basic needs, including social-emotional ones. When a child’s personal safety is at risk (real or perceived), or when a child is unable to show appropriate emotions, incapable of developing positive relationships, or cannot manage their emotions effectively, we know that teaching English, math, science, and social studies becomes secondary. What must be considered is how to ensure that a child’s social-emotional state is intact and grounded so that they can perform at higher academic levels. Educators should be seeking out the various SEL curricula and strategies that are available and infuse them into—not replace—their academic curriculum.

SEL Training

I’m not trained to do that! is a comment heard all too often by educators who are asked to address a child’s needs beyond the academic content. Children no longer arrive in classrooms ready for academic learning. There are so many obstacles and barriers that children face today that did not exist in years past.

Educators cannot act as independent contractors. Whether ready for it or not, educators are in a position to help assess and address the various needs that students may have, especially social-emotional needs. In an attempt not to promote one training over another, educators and parents must be aware of the various trainings that exist, and that local schools and area education agencies can help direct them to the training that will work best for them. Many factors need to be considered when reviewing the various SEL trainings, including whether the trainer is an expert in SEL skills, what age group the training material targets, cost of the material, and relevancy and application of the material.

Quality training for educators and families in social-emotional learning should cover five critical standards:

- Self-awareness

- Self-management

- Responsible decision-making

- Social awareness

- Relationship skills

Learning around these five standards is vital to the teaching/parenting and understanding of social and emotional learning at school and/or home. When seeking out social-emotional training, it is important to look for these connections in the training and how outcomes are embedded throughout these standards. In addition, educators and parents will want to research the facilitator’s expertise in the area of social-emotional learning and experience as an educator. The most beneficial training will be presented by a person experienced in both social-emotional learning and educational strategies.

School Services

Teachers are expected to meet both the content and social-emotional needs of those children who come to school lacking social-emotional skills. Families, on the other hand, can find themselves at a loss as to how to support their child who may be struggling with social-emotional challenges. It is in that partnership of educators and family that both can find success. Many educators and families are unaware of the number of resources that are available to them even though schools are often connected to a variety of services that students may need when addressing social-emotional learning. In our experience, we have found that families and classroom teachers are often the least aware of these available supports.

One support to consider is the school’s counseling department. School counselors have a large role in today’s educational setting, and addressing the social-emotional needs of students is a major focus for them. School counselors are professionals trained in addressing and implementing social-emotional learning. At the elementary level, many school counselors teach social-emotional learning lessons to supplement a child’s core academic learning. At the secondary level, school counselors will infuse social-emotional learning into their counseling of students who are struggling. In either case, the school counselor is a support available for students, educators, and parents.

Another support for social-emotional learning is the school nurse. Nurses often see the symptoms of social-emotional imbalance. When students go to the nurse for physical sickness, they may also seek support for emotional needs. The nurse is often the one who notifies administrators, counselors, teachers, and parents of concerns around a student’s emotional struggles. A classroom teacher or parent should not hesitate to ask the nurse to evaluate the child for social-emotional needs. Keep in mind that a nurse is trained to evaluate mental health as well as physical health. A nurse will not engage in counseling, but they can certainly assess whether a child should be seen by the school counselor or a professional therapist. A school nurse values keeping a child in class whenever possible, but they are most apt to initiate problem-solving meetings with parents and school officials when needed.

Last, the school-family partnership is a support that often goes undetected but is one that schools desperately desire to have with families. Parents should never hesitate to call the school if there are concerns about their child. The proverb “it takes a village to raise a child” is most relevant, especially in today’s society. It is the collective duty and responsibility of the school-family partnership to provide a safe and healthy environment for children so that they can develop, flourish, and be able to realize their hopes and dreams (Reupert et al., 2022). Educators must realize that families have firsthand knowledge of their children and can be a vital partner in meeting any of a child’s unmet social-emotional needs that are hindering academic learning. Educators and families should be quick to connect and partner when attempting to address social-emotional challenges their child is experiencing, whether it is in school or at home.

As young people grow, they need an environment in which they can make mistakes and grow with caring adults who will teach and guide them and not ignore or ridicule them (Borba, 2021). These stages of development prepare children for life’s stresses and challenges. Gaining these social-emotional skills early on will make children more resilient and capable of handling the unthinkable as adults.

A Social-Emotional Story

It was a cold February evening in rural Iowa. I had finally gotten home from a long, exhausting day as an educational leader in a public high school. After my dinner and a quick shower, I relaxed in the recliner to catch up on the hundred-plus unread emails I had. After scanning the first 20 emails, the next one caught me off guard:

Dr. Hayes—This has been the hardest week of my life! Going through things I found this and figured 20 years ago I never told you the feeling was mutual. I still talk to this day about how much I enjoyed you as a principal and how much respect I had for you for being fair with me and my shenanigans!

Attached to the email was a photo of the graduation card that I had written to this young man 20 years before, when he was a student of mine:

John, It has been a real pleasure to know you. I really appreciate the respect you have shown me (even when it was tough to do). You are a great guy, John, and I will miss seeing you around. Try to stay out of trouble 🙂 Congrats. Mr. Hayes.

I sat stunned. Why would this young man hold on to a card like that for 20 years? I read that card many times over trying to see if there was anything special about what I said. Then I thought, It’s not in the words; it is in his heart!

As educators, we can often forget the power our words and actions have with our students. I thought about those “shenanigans” John and many like him participated in over the years, and smiled. This is the why of what I do, I thought. Making sure kids like John feel valued and loved no matter what they have done. Let’s be honest: Kids will be involved in “shenanigans.” They are kids, after all. And that is the time they will test boundaries, make impulsive decisions, and push the limits. It’s during this time that children need loving adults who will hang in there with them as they learn to make good decisions.

I began to wonder about the first sentence of his email: “This has been the hardest week of my life!” What might he be going through and what support does he have? How can I support him now? How did my words from 20 years ago support his current social-emotional needs? And what role did I and others have in developing his abilities to sustain challenges?

Later that evening he responded to my email asking about his situation. It turns out John’s wife had unexpectedly passed away the previous week. He had been going through pictures with his young daughter and found my graduation card to him, which he had forgotten about. It reminded him of something from his school days, and he related to me how he told his in-laws about when he had broken a window at school and how I handled the situation and the mutual respect that we had. John wanted to reach out and tell me, and decided to email me earlier that day.

After some time had passed, I checked in on John to see how he was doing.

Not too bad. Missing her isn’t going away anytime soon, but busy figuring out how to do both roles so every day flies by. Every day is a little better. Still have tough moments for sure. It will never be the same, but the friends and family we have surrounded ourselves with have made an extremely difficult time much easier!

John reminded me that when families and schools develop social-emotional skills in kids, enduring challenges in life becomes possible.

—Kenneth Hayes

See article references here.

Kenneth Hayes

Kenneth Hayes, EdD, has been an educator for 30 years. He began as a middle school and high school teacher, coach, and club sponsor, and has been a high school administrator for 19 of those years. He’s currently the program coordinator for the University of Northern Iowa’s Principal Preparation Program, training aspiring administrators on divergent ways to improve on the social-emotional needs of students and through these efforts have a positive impact on student achievement.

Angila Moffitt

Angila Moffitt, EdD, began her teaching career as a special education teacher at the elementary and high school grade levels, both in brick-and-mortar and online formats. After several years of teaching, her passion for education led her to become a principal of an elementary school, where she started the first school-daycare combination in the area. Following her passion for training teachers and leadership, Angila is currently the director of the Early Childhood Program and the EDAD Principalship Program at Northwestern College and a professor of graduate studies at Northwestern College. She also serves as a dissertation chair for students at the American College of Education.