By Norris M. Haynes

Introduction

Students who experience overall academic and nonacademic school success tend to demonstrate high levels of what Goleman (1995) calls “emotional intelligence,” or EQ. We may think of EQ as having two major dimensions, internal and external. The internal dimension is concerned with the student’s capacity to recognize, monitor, manage, and express their feelings in appropriate and healthy ways. The external dimension is concerned with the student’s capacity to interact in socially acceptable ways with peers and adults, which includes being aware of the feelings and needs of others and responding in appropriate ways. These two dimensions are consistent with Gardner’s (2011) notions of intrapersonal and interpersonal intelligences. Maladaptive behaviors such as school violence and bullying, and negative school outcomes that include dropping out of school, disinterest, and underachievement, are linked to the inadequate social and emotional development of students (CASEL, 2003).

In general, the literature supports the contention that social competence and psychological well-being are significantly related to academic achievement and general school success. Students can learn to the full extent of their abilities if they are under less psychological duress or can adjust well to stressful situations. Schools can address students’ social and emotional development and their capacity to be resilient in difficult circumstances by helping students to develop their social and emotional skills. Educators—including teachers, school psychologists, counselors, social workers, and school administrators—are best prepared to respond to the social and emotional needs of students if they have a basic understanding of how the cognitive and emotional centers of the brain work and how they are connected to each other and impact student learning and outcomes. Advances in brain imaging techniques have enhanced understanding of the structural and chemical relationship between emotions and cognitions. The field of social and emotional learning (SEL) takes what has been learned from neuroscience about the relationship between emotions and cognitions and then advances the practical applications of this knowledge by identifying critical SEL skills that are tied to successful academic and social performance indicators. The evidence from neuroscience is clear that emotions influence cognition and vice versa (De Houwer & Hermans, 2010).

Brain Structures and Processes in Cognition and Emotions

The limbic system, or emotional center of the brain, has a significant role in the processing of emotions and memory. Specifically, the amygdala, the principal structure in the limbic system, helps to filter sensory information and initiate an appropriate response. It also influences early sensory processing and higher levels of cognition. The amygdala, made up of two almond-shaped fingernail-size structures, adjoins the hippocampus, which helps to convert short-term memory into long-term memory and influences its functioning. Thus, emotional responses affect memory. Research has shown that the emotional centers of the brain are linked to the cortical areas, where cognitive learning takes place (Kuhlmann et al., 2005; Tollenar et al., 2009). Some researchers suggest that the emotional centers of the brain in times of stress tend to hijack the cognitive centers of the brain, thus making it difficult for individuals to think, concentrate, or problem solve effectively. Sousa (2011) noted:

There is a hierarchy of response to sensory input. Any input that is of higher priority diminishes the processing of data of lower priority. The brain’s main job is to help its owner survive . . . Emotional data also take high priority. When an individual responds emotionally to a situation, the older limbic system (stimulated by the amygdala) takes a major role, and the complex cerebral processes are suspended. (p. 47)

It is known that many more neural fibers extend from the brain’s emotional center in the limbic system to the logical/rational cortical center than the reverse. The influence of the emotional brain center is greater on the logical cognitive brain center than the reverse (Erlich et al., 2012; LeDoux, 2012).

Brain imaging studies provide scientific confirmation of and underscore the role that emotions play in cognition (Sousa, 2011). Phelps (2006), in reporting on some brain studies, noted, “[T]raditional approaches to the study of cognition emphasize an information-processing view that has generally excluded emotion. In contrast, the recent emergence of cognitive neuroscience as an inspiration for understanding human cognition has highlighted its interaction with emotion” (p. i). She concluded from her review of neuroscience evidence that emotions and cognitions are intertwined from perception to reasoning, and an understanding of human cognition requires that emotions be considered. Bush et al. (2000) noted that neural-imaging studies indicate that areas of the anterior cingulated cortex (ACC), part of the brain’s limbic or emotional system, are involved in cognition. Gray et al. (2002) used functional MRI to test the hypothesis that the fact that emotional experiences influence cognitive processes in the prefrontal cortex is evidence that emotions and cognition are integrated. They concluded that emotions and higher-order cognitive processes are fully integrated; that is, during processing, emotions and cognition appear to contribute equally to how we think and behave. It is this integration of emotion and higher cognition, and the reciprocal influences of the cortical and rational brain centers, combined with strong educational research, that form the empirical neurological basis for the five SEL and academic social and emotional learning (ASEL) competencies: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making. These competencies combine and integrate elements of emotions and cognition.

Davidson and Begley (2012) pointed to data showing that when the brain’s centers for distress are activated, they impair the functioning of the areas involved in memory, attention, and learning. In other words, because of the way our brains are wired, emotions can either enhance or inhibit the ability to learn. Teaching social and emotional skills makes great sense. Because of the neuroplasticity of the brain, experiences that are repeated and reinforced can shape the brain. Davidson and Begley (2012) found that the more a child practices self-discipline, empathy, and cooperation, the stronger the underlying circuits become for these essential life skills. Davidson (n.d.) noted:

In parallel with the development and promotion of SEL is the neuroscience evidence that establishes some of the key circuits that underlie the core competencies in popular models of SEL. For example, there is a large body of neuroscientific evidence on self-management that includes the growing understanding of the circuits critical for emotion regulation and delay of gratification.

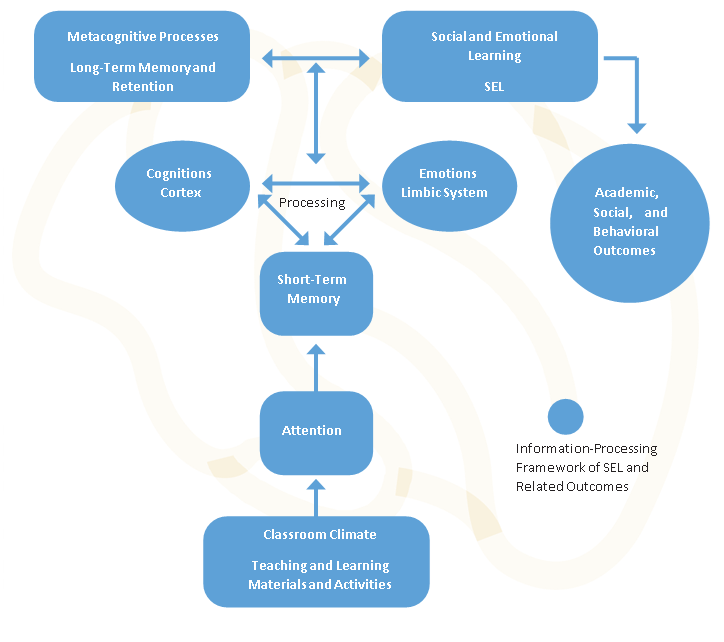

The figure below illustrates an information- processing conceptual framework that demon- strates how the interaction between cognition and emotions influences SEL and related outcomes. When applied to classrooms, information processing begins with students attending to informational cues, both verbal and nonverbal, that enter the brain into the students’ working or short-term memory. How this information is processed emotionally and cognitively influences how much and how well this information enters longer-term memory, is retained, and becomes part of a more internalized schema that facilitates understanding and metacognitive processes that include reflection, problem-solving, and planning. These processes are significantly influenced and mediated by the emotional messages coming from the limbic system. SEL influences the emotional messages that impact metacognitive processes, and these in turn influence SEL and related outcomes.

SEL Competencies

Over the past decade, SEL has become a significant and perhaps essential concept in any serious discourse about improving children’s overall development, including their academic development. Working on his groundbreaking work on EQ, Goleman (1995) asked and answered two basic and compelling questions about the most essential factors that contribute to success in school and in life:

What can we change that will make our children fare better in life? What factors are at play, for example, when people of high IQ flounder and those of modest IQ do surprisingly well? I would argue that the difference quite often lies in the abilities called here emotional intelligence, which include self-control, zeal and persistence, and the ability to motivate oneself. And these skills, as we shall see, can be taught to children, giving them a better chance to use whatever potential the genetic lottery may have given them. (p. xii)

Elias et al. (2002) noted the potential of SEL as a significant focus among educators in addressing student development and student achievement:

If IQ represents the intellectual raw material of student success, EQ is the set of social-emotional skills that enables intellect to turn into action and accomplishment. Without EQ, IQ consists more of potential than actuality. It is confined more to performance on certain kinds of tests than to expression in the many tests of everyday life in school, at home, at the workplace, in the community. (p. 4)

Some research also indicates that EQ can be equal to or a better indicator of life success than IQ (Ross et al., 2002). SEL then may be viewed as the actuation or activation of EQ in measurable and teachable skill sets that “enable the successful management of life tasks such as learning, forming relationships, solving everyday problems, and adapting to the complex demands of growth and development” (Elias et al., 1997, p. 2).

The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) and others have identified five groups of interrelated core academic, social, and emotional competencies that ASEL programs should address and that can and should inform the strengthening and development of more robust assessment tools

(CASEL, 2003). When students practice these five basic SEL principles and integrate them effectively into their educational experiences, they are much more likely to enjoy a successful school experience (Durlak et al., 2011; Greenberg et al., 2003; Zins et al., 2004). The five competence domains are:

- Self-awareness: Being able to identify and describe one’s feelings, needs, desires, and motivations. For example, a student who is being called names and is being picked on by his peers can recognize his feelings of sadness and describe what it feels like to experience this. He will also be able to think about and express a different narrative about himself that reflects who he truly is as a person. A student who is more aware of their learning needs as well as their academic strengths and shortcomings is better positioned to maximize strengths and to get help in areas that need improvement, and thus is more likely to succeed academically.

- Self-management: The ability to monitor and regulate one’s feelings and one’s behavior. A student who practices effective self-management can monitor and regulate their emotions and impulses while demonstrating self-regulatory behaviors. These practices may include but are not limited to good anger management, effective time-management skills, the ability to establish short- and long-term goals, delay gratification, and show the self-control and self-discipline needed to succeed academically.

- Social awareness: Being sensitive to one’s social environment and having knowledge of how to recognize, empathize with, and respond appropriately to the feelings and behaviors of others. The implications of social awareness for academic success and as an inherently important aspect of teaching and learning are significant. Students who understand how their behaviors affect other students and who can regulate and modify their interactions with teachers and other adults are more likely to succeed academically.

- Relationship skills: One’s ability to interact effectively and establish healthy reciprocal relationships with others. Building relationship skills among students in early grades helps students learn how to cooperate with others in performing learning tasks. They develop friendships and avoid negative feelings of being socially isolated, which can impact their love for school and learning. In high school, relationship skills are critical to gaining acceptance, influencing and leading others, and building the kinds of social networks that can be useful beyond high school. Students who can work cooperatively with other students and who respect and are able to learn more from adults are better positioned to succeed academically.

- Responsible decision-making: Making thoughtful, constructive, and healthy decisions based on careful consideration and analysis of information. When students make responsible decisions about studying, managing their time well, completing and submitting academic assignments on schedule, preparing for tests, and doing what it takes to succeed in school, they are more likely to experience academic success.

When students make responsible decisions about studying, managing their time well, completing and submitting academic assignments on schedule, preparing for tests, and doing what it takes to succeed in school, they are more likely to experience academic success.

The implementation of SEL programs in schools can be an effective strategy to prevent emotional and behavioral problems among students (Caldarella et al., 2009). SEL competencies help lower the occurrence of high-risk behaviors and empower students to deal effectively with daily social and academic challenges (Durlak et al., 2011; Greenberg et al., 2003). DeAngelis (2010) noted that “while SEL programs vary somewhat in design and target different ages, they all work to develop core competencies: self-awareness, social awareness, self-management, relationship skills and responsible decision-making” (p. 46). Research has shown that some SEL programs are effective in facilitating academic learning (Zins et al., 2004). SEL programs are extremely versatile and can be implemented in many different environments, including home and school, and with children of varying ages as well as with adults. SEL programs can be used with children who attend public or private schools as well as with children who are homeschooled, and these programs can be incorporated effectively into existing school curricula and initiatives (Devaney et al., 2006).

Evidence of SEL Effects

The positive effects of SEL on a range of academic, social, and behavioral indicators in school and out of school are very well documented. Davidson (n.d.) noted:

Interventions designed to promote SEL have been empirically studied and the scientific findings clearly show gains on various proximal measures of social and emotional competencies. The evidence also demonstrates improvements on distal measures such as traditional academic metrics and even on standardized test scores. The available body of evidence strongly suggests that interventions focused on social and emotional learning are helpful in promoting effective emotion regulation, the setting and maintaining of positive goals, empathy toward others, establishing and maintaining positive social relationships and making responsible decisions. Moreover, SEL programs can act preventatively to minimize the likelihood of bullying, antisocial behavior, excessive risk-taking, anxiety, and depression. Investment in early interventions to promote SEL clearly provide a return on investment that far exceeds by several-fold the cost of such programs. It is for all of these reasons that widespread dissemination of SEL programs globally is so important.

For those SEL programs that have established assessment measures, the growing evidence seems to indicate a clear linkage between SEL competencies and improvements in academic outcomes. Greenberg et al. (2003) and Zins et al. (2004) identified strong linkages between SEL competencies and academic achievement. Both studies examined the relationships between social-emotional education and school success, focusing specifically on interventions that improve student learning. The studies provided scientific evidence and examples that support the important impact of ASEL on academic achievement by helping to build skills connected to cognitive development, achievement motivation, and positive interpersonal relationships.

A research synthesis of 213 studies of SEL programs showed that SEL considerably improved children’s behavior, attitudes, grade point average, and performance on standardized tests (Durlak et al., 2011). In contrast to students who did not receive the SEL implementation, students in the SEL programs had fewer school absences and did better academically, showed less disorderly behavior and had fewer suspensions, and in general enjoyed school more. Durlak et al. (2011) concluded that SEL improves children’s relationships with others, motivates them to learn, and is effective in reducing disruptive, violent, and drug-using behaviors. They also reported that students who participated in SEL programs score 11 percentage points higher on achievement tests when compared with students who did not participate in an ASEL program. Taylor and Dymnicki (2007) analyzed a subset of 34 studies looking at the effects of SEL on students’ grades and performance on achievement tests. The results showed that an ASEL curriculum improved students’ school functioning, with effect sizes ranging from 0.20 to 0.39 on positive social behavior, attitudes, discipline, attendance, grades, and achievement tests.

A research synthesis of 213 studies of SEL programs showed that SEL considerably improved children’s behavior, attitudes, grade point average, and performance on standardized tests.

Payton et al. (2008) reported on three large reviews of 317 studies with 324,303 children. The reviews were organized in three parts to demonstrate the effectiveness of ASEL programs on elementary and middle school students: the universal review (which includes studies from the Durlak et al. [2011] meta-analysis), the indicated review, and the after-school review. The overall finding indicated that students in SEL programs showed improvement in their personal, social, and academic lives. ASEL students also showed gains in achievement test scores of 11 to 17 percentile points. Participation in SEL programs showed efficacy in the school and after-school programs, and follow-up data suggested that these interventions produced benefits over time. However, long-term effects were not as strong as short-term effects. The universal and indicated reviews showed ASEL programs to be effective when implemented by school staff. The three reviews also indicated that universal and after-school SEL programs demonstrated that those following the SAFE process were more effective than other programs. As explained in Payton et al. (2008), SAFE refers to:

- Sequenced: Does the program apply a planned set of activities to develop skills sequentially in a step-by-step fashion?

- Active: Does the program use active forms of learning such as role-plays and behavior rehearsal with feedback?

- Focused: Does the program devote sufficient time exclusively to developing social and emotional skills?

- Explicit: Does the program target specific social and emotional skills?

Programs that exemplify the SEL approach include:

- Seattle Social Development Study (Hawkins et al., 2001)

- Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies (Greenberg & Kusché, 1998; Kam et al., 1999)

- Responsive Classroom (Elliott, 1993, 1995a, 1995b)

- Caring School Community (Battistich, 2001; Battistich et al., 1989, 1996, 2000)

- Social and Emotional and Character Development (Elias, 2008)

- RULER (Brackett, 2010)

Conclusion

SEL is rooted in an understanding of how the brain processes and responds to information and is informed by evidence that the emotional and cognitive brain centers are inextricably and reciprocally connected. When educators teach students they activate a dynamic interaction between the emotional and cognitive brain centers, which in turn influences student learning and behavior. SEL interventions help to mediate and moderate the cognitive-emotional dynamic, which in turn influences and modifies outcomes. Therefore, SEL provides teachers and other school-based professionals with a scientifically grounded and evidence-based way to positively impact student learning and behavior.

Dr. Norris M. Haynes is the director of the Center for Community and School Action Research at Southern Connecticut State University. He is also a licensed psychologist, a fellow of the American Psychological Association, and a diplomate in the International Academy of Behavioral Medicine, Counseling and Psychotherapy. Norris was also a member of the founding leadership team of the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning and is founding executive director of Educational and Psychological Solutions, LLC. He has published extensively.